Vivek Ramaswamy’s.

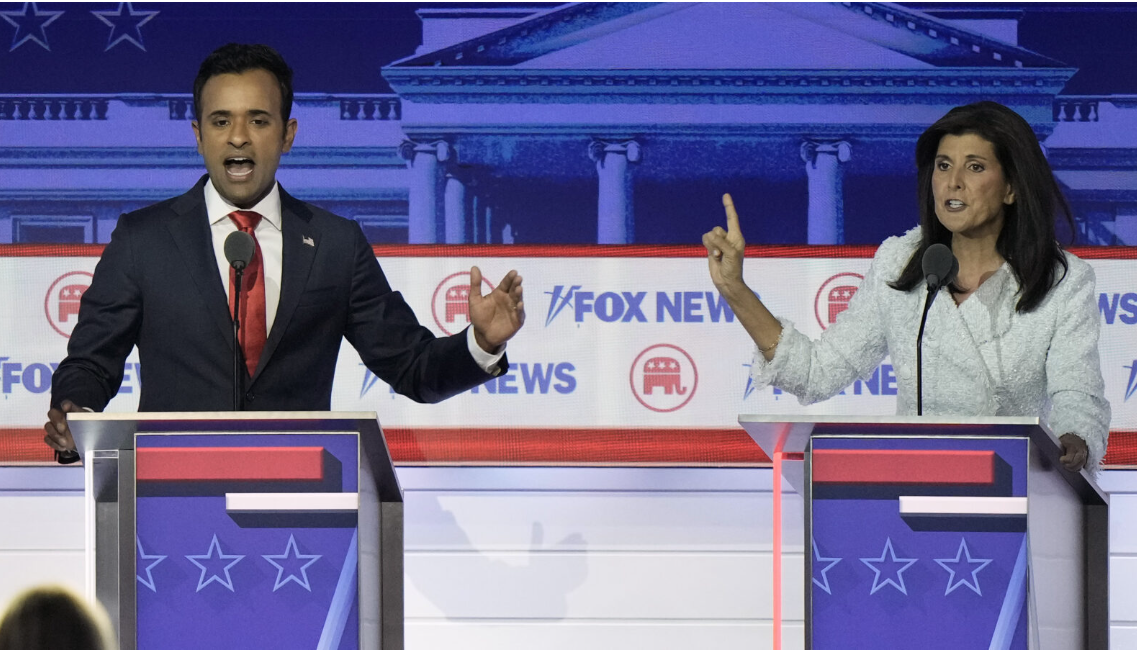

Vivek Ramaswamy’s The youngest candidate on Wednesday night’s debate stage didn’t make any friends among his fellow Republican presidential hopefuls, questioning their morality, mocking their promises, and suggesting that he, by virtue of his inexperience in government, was ideally suited to solve a nation’s problems.

For Vivek Ramaswamy, it was familiar territory.

Long before he was explaining Perestroika to Mike Pence and congratulating Nikki Haley on a future career in the defense industry, Ramaswamy brought a similar brashness to biotech. In 2015, he was a 29-year-old hedge fund manager, fresh out of Yale Law School, lecturing the trillion-dollar pharmaceutical industry on how it was going about the business of drug development all wrong.

His company, called Roivant, would outfox the Pfizers and Mercks of the world by seeing the hidden value in medicines they were too bureaucratically blinkered to figure out for themselves, in the process creating “the highest return on investment endeavor ever taken up in the pharmaceutical industry,” he told Forbes at the time. Vivek

And much like at Wednesday’s debate, where Ramaswamy both met raucous cheers and occasionally had to shout over thundering boos, he proved to be polarizing. At his start, some of his biotech colleagues praised him as a visionary, an outsider shaking up an industry that had grown sclerotic at its highest ranks. Others saw a profiteer cashing in on what was then a historic boom for biotech, a speculator with a one-weird-trick business plan that was more likely to make him and his hedge fund friends rich than make any new medicines. Vivek Ramaswamy’s

“I know I run the risk of looking like a fool two or three years from now,” one Massachusetts Institute of Technology business professor said in 2016, “but this sounds like some people are being bamboozled.

A year later, the first test of Ramaswamy’s boundless confidence ended in embarrassment, when an Alzheimer’s disease treatment plucked from pharmaceutical obscurity failed in a closely watched clinical trial, erasing $2 billion in value and lending credence to the notion that Roivant’s purportedly revolutionary business model was too clever by half. Vivek

“I am sorry for the people who bought into the hype, and I’m sorry for Alzheimer’s patients and families who had hopes for this compound,” the biochemist Derek Lowe wrote on his blog after the failure. “But frankly, I see the entire effort as a misuse of funds — Alzheimer’s research would have been better off if the same amount of money had been applied almost anywhere else in the field.”

The “failure is challenging and humbling for me on a deeply personal level,” Ramaswamy wrote in a letter to employees. “While this is personally difficult for me, that may not be a bad thing for our business: I will be sure to harness the ‘sting’ I feel now to double down on my efforts to ensure that we succeed as a company, and that Roivant will be even stronger for having dealt with the experience of failure.

Ramaswamy, by then biotech’s most famous millennial not named Martin Shkreli, had already built in contingency plans. Roivant had a pipeline of medicines, developed by an ever-increasing number of subsidiaries, and Ramaswamy’s fundraising prowess had secured its future with billions of dollars from investors including SoftBank and Viking Global. Vivek

In 2021, Ramaswamy ceded the CEO role and became executive chairman. Roivant had become less a brash disruptor and more of a normal drug company. By February 2023, when Ramaswamy left the company entirely to mount his presidential campaign, Roivant had six Food and Drug Administration-approved medicines and another dozen or so drugs in late-stage development.

Whether it can fulfill Ramaswamy’s foundational promise of becoming the single greatest return on investment in industry history remains to be seen, but it’s worth about $9 billion, and the Pfizers and Mercks it once sought to displace are reportedly interested in buying it.